CounterPunch, August 13, 2012

The revelation about President Barack Obama’s decision to provide secret American aid to Syria’s rebel forces is a game changer. The presidential order, known as an “intelligence finding” in the world of espionage, authorizes the CIA to support armed groups fighting to overthrow Bashar al-Assad’s government. But it threatens far more than the regime in Damascus.

The revelation about President Barack Obama’s decision to provide secret American aid to Syria’s rebel forces is a game changer. The presidential order, known as an “intelligence finding” in the world of espionage, authorizes the CIA to support armed groups fighting to overthrow Bashar al-Assad’s government. But it threatens far more than the regime in Damascus.

The disclosure took its first casualty immediately. Kofi Annan, the special envoy to Syria, promptly announced his resignation, bitterly protesting that the UN Security Council had become a forum for “finger-pointing and name-calling.” Annan blamed all sides directly involved in the Syrian conflict, including local combatants and their foreign backers. But the timing of his resignation was striking. For he knew that with the CIA helping Syria’s armed groups, America’s Arab allies joining in and the Security Council deadlocked, he was redundant.

President Obama’s order to supply CIA aid to anti-government forces in Syria has echoes of an earlier secret order signed by President Jimmy Carter, also a Democrat, in July 1979. Carter’s fateful decision was the start of a CIA-led operation to back Mujahideen groups then fighting the Communist government in Afghanistan. As I discuss the episode in my book Breeding Ground: Afghanistan and the  Origins of Islamist Terrorism (chapters 7 & 8), the operation, launched with a modest aid package, became a multi-billion dollar war project against the Communist regime in Kabul and the Soviet Union, whose forces invaded Afghanistan in December 1979. In the following year, Carter was defeated by Ronald Reagan, who went for broke, pouring money and weapons into Afghanistan against the Soviet occupation forces to the bitter end.

Origins of Islamist Terrorism (chapters 7 & 8), the operation, launched with a modest aid package, became a multi-billion dollar war project against the Communist regime in Kabul and the Soviet Union, whose forces invaded Afghanistan in December 1979. In the following year, Carter was defeated by Ronald Reagan, who went for broke, pouring money and weapons into Afghanistan against the Soviet occupation forces to the bitter end.

Carter’s national security adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski later claimed that it was done on his recommendation, and that the motive was to lure Soviet forces into Afghanistan to give the Kremlin “its Vietnam.” The Soviets’ humiliating retreat from Afghanistan in 1989, the collapse of Soviet and Afghan communism and the rise of the Taliban triggered a chain reaction with worldwide consequences. President Obama’s decision to intervene in support of Syria’s rebels, who include fundamentalist Islamic fighters, points to history repeating itself. Brzezinski, now in his 85th year, still visits Washington’s corridors of power. And General David Petraeus, a formidable warrior, is director of the CIA.

Three decades on, it seems likely that President Carter’s motive behind signing the secret order to provide aid to the Mujahideen was to entice the Soviets into Afghanistan’s inhospitable terrain, thus keeping their military away from Iran in the midst of the Islamic Revolution which overthrew America’s proxy, Shah Reza Pahlavi, in February 1979. If that was indeed the plan, then the Soviet leadership fell right into the Afghan trap.

China was then part of the U.S.-led alliance against the Soviets. Now Beijing and Moscow stand together against Washington as the conflict in Syria escalates. Otherwise, the U.S.-led alliance has many of the old players––the much enlarged European Union, Saudi Arabia, Qatar and others in the Sunni bloc in the Arab world. And Turkey, which is now the base for the anti-Assad forces, channeling help to them. Turkey’s Islamist government plays a crucial role in Syria, like Pakistan in the 1980s during America’s proxy war in Afghanistan.

In Washington, an American official told Reuters that “the United States was collaborating with a secret command center operated by Turkey and its allies.” And a few days before, the news agency reported that Saudi Arabia, Qatar and Turkey had established a “nerve center” in Adana in southern Turkey, near the Syrian border, to coordinate their activities. The place is home to America’s Incirlik air base and military and intelligence services.

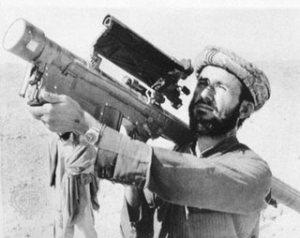

According to NBC News a few days ago, the rebel Free Syrian Army has acquired American MANPAD Stinger missiles via Turkey, clearly to target Syrian government aircraft. It reminds of President Reagan’s decision in the mid-1980s to supply Stingers to Mujahideen groups for use against Soviet aircraft. Their use was first reported in 1987 and it soon emerged that the heat-seeking weapons were so accurate that they were hitting three out of four aircraft in Afghanistan. As I have discussed in my book Breeding Ground, some of the hundreds of Stingers were likely to have been passed on to the Taliban and their allies after the Soviet forces left Afghanistan and the last Communist government in Kabul collapsed in 1992.

According to NBC News a few days ago, the rebel Free Syrian Army has acquired American MANPAD Stinger missiles via Turkey, clearly to target Syrian government aircraft. It reminds of President Reagan’s decision in the mid-1980s to supply Stingers to Mujahideen groups for use against Soviet aircraft. Their use was first reported in 1987 and it soon emerged that the heat-seeking weapons were so accurate that they were hitting three out of four aircraft in Afghanistan. As I have discussed in my book Breeding Ground, some of the hundreds of Stingers were likely to have been passed on to the Taliban and their allies after the Soviet forces left Afghanistan and the last Communist government in Kabul collapsed in 1992.

In recent months, American and European officials have been busy feeding information to media outlets that Saudi Arabia and Qatar are the main sources of weapons to rebels in Syria through Turkey. The pattern is consistent with the long-standing Saudi policy to keep Islamists out of Saudi Arabia itself, lest they challenge the ruling family. Long-term lessons of proxy wars remain unheeded for immediate perilous “gains.”

Reports of the Obama administration sending Stinger missiles to Syrian rebels carry the first indication that non-state players now have advanced U.S. weaponry in the Middle East. That Washington is in such a cozy alliance with forces including Islamists soon after the killing of Osama bin Laden on Obama’s personal order is as incredible as it is consistent with follies of the past. The present will define the future again.

The situation in Egypt is becoming explosive. The killing of 16 Egyptian border guards in the Sinai Peninsula by “suspected Islamists,” and violence thereafter, represent challenges on several fronts for the new president Mohamed Morsi. Israel has been quick to blame Islamic militants in Gaza, ruled by Hamas, which has close ties with the Muslim Brotherhood, the party of the Egyptian president. For  its part, the Brotherhood has pointed the finger at Israel’s secret service Mossad, claiming it is a plot to thwart Morsi’s presidency. These developments cast a shadow over Morsi’s relations with Hamas and, at the same time, increase his dependence on the Egyptian armed forces to quell the unrest, thereby undermining his authority. Murderous optimism of powerful and suicidal pessimism of victims in an oppressive environment blight the lives of many.

its part, the Brotherhood has pointed the finger at Israel’s secret service Mossad, claiming it is a plot to thwart Morsi’s presidency. These developments cast a shadow over Morsi’s relations with Hamas and, at the same time, increase his dependence on the Egyptian armed forces to quell the unrest, thereby undermining his authority. Murderous optimism of powerful and suicidal pessimism of victims in an oppressive environment blight the lives of many.

[END]

You must be logged in to post a comment.