Academic Corridor, January 9, 2013

The Czech writer Milan Kundera, who was twice expelled from the Communist Party, forced to leave his homeland to go to live in France seven years after the 1968 Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia, then stripped of his Czech citizenship, wrote about humiliation in his novel, Immortality: “The basis of shame is not some personal mistake of ours, but the ignominy, the humiliation we feel that we must be what we are without any choice in the matter, and that this humiliation is seen by everyone.” These words capture the potent emotion that humiliation is––whether it applies to an individual, a community or nation. The bigger the group that feels humiliated, the greater the chance that the humiliator’s act will have far-reaching consequences.

I discuss the role of shame in my forthcoming book, Imperial Designs: War, Humiliation and the Making of History, the final volume of a trilogy. Imperial Designs follows Breeding Ground, which is a study of Afghanistan from the 1978 Communist coup to 2011. Based on Soviet and American archives, Breeding Ground covered the gradual disintegration of the Afghan state, the Soviet invasion of December 1979, America’s proxy war against the Soviet forces in the 1980s, the collapse of Soviet and Afghan communism around 1990, the rise of the Taliban and the creation of safe havens for groups like al Qaida, the circumstances of America’s return to Afghanistan after the events of September 11, 2001 and the war thereafter. The second book, Overcoming the Bush Legacy in Iraq and Afghanistan, evaluates George W. Bush’s presidency in terms of the “war on terror,” and focuses on the invasions of both Afghanistan and Iraq and their aftermath.

I had suggested in these two books that among the factors contributing to the events of September 11, 2001 was a sense of humiliation felt in the Muslim world, especially in the Middle East. The history of Arabs and Persians is rich and interesting. They have both fought numerous wars over the centuries. External actors’ meddling in the region, by the Ottomans, then the British and the Americans is intriguing. The consequences have been profound and far-reaching.

The collapse of the Ottoman Empire around the First World War in the early twentieth century and its aftereffects; the discovery of oil in the region and the division of lands between Britain and France; the creation of the state of Israel after the Second World War and its meaning for Palestinians and Arabs; and further conflicts. In Iran, the early democracy movement; the 1953 overthrow of the elected government of Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddeqh in an Anglo-American intelligence plot; and subsequent events over a quarter century until the overthrow of the Pahlavi dynasty in the 1979 revolution. Examination of events such as these is relevant in any study of the role of humiliation and the shaping of the contemporary Middle East.

The upheavals of recent decades in the region have their origins in the events around the First World War a century before, when Ottoman rule was replaced by British and French colonial rule using the instrument of “Mandate.” Conflict between tribes and wars with external invaders have determined the thinking and behavior of local peoples through history. Vast sandy deserts, a free spirit and a warrior instinct are fundamental elements of Middle Eastern cultures. Repeatedly, wars put those instincts on display and reinforced them.

Where desert communities were sparsely located, interaction was less between them, but more within members of each community or tribe. The emphasis was on cohesion within each tribe. Personal possessions within the general populous were fewer; lifestyle was frugal for most members. Wealth tended to accumulate with chiefs. Honor, its dispossession causing humiliation, and promises betrayed became strong drivers of human behavior. Defending the honor of a person, a clan, tribe or nation––and regaining it after humiliation––became of utmost importance. Past injustices and unsettled disputes still persist. More have been added to the long list in the new century, and we have lived only through the first decade.

One of the earliest references to imperial behavior in literature can be found in Plato’s Republic. There is a dialogue between Socrates and Glaucon about rapid development in society. The essence of that dialogue is that increase in wealth results in war, because an enlarged society wants even more for consumption. Plato’s explanation is fundamental to understanding the causes of war. This is how empires rise, military and economic power being essential to further their aims. A relevant section in Plato’s Republic reads, “We shall have to enlarge our state again. Our healthy state is no longer big enough; its size must be enlarged to make room for a multitude of occupations none of which is concerned with necessaries.”

Nearly two and a half millennia after Plato, Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri offered a Marxist interpretation of neo-imperialism in the twenty-first century in their book, Empire. Their core argument in the book, first published in 2001, was that globalization did not mean erosion of sovereignty, but a set of new power relationships in the form of national and supranational institutions like the United Nations, the European Union and the World Trade Organization. According to Hardt and Negri, unlike European imperialism based on the notions of national sovereignty and territorial cohesion, empire now is a concept in the garb of globalization of production, trade and communication. It has no definitive political center and no territorial limits. The concept is all pervading, so the “enemy” must be someone who poses a threat to the entire system––a “terrorist” entity to be dealt with by force. Written in the mid-1990s, Empire got it right, as events thereafter would testify.

Johan Galtung said in 2004––at an early stage of the “war on terror”––something that looks like a fitting definition of the term “empire.” Galtung described it as “a system of unequal exchanges between the center and the periphery.” For empire “legitimizes relationships between exploiters and exploited economically, killers and victims militarily, dominators and dominated politically and alienators and alienated culturally.” Galtung observed that the U.S. empire “provides a complete configuration,” articulated in a statement by a Pentagon planner. That Pentagon planner was Lt. Col. Ralph Peters, who wrote in his 1999 book Fighting for the Future: Will America Triumph?: “The de facto role of the United States Armed Forces will be to keep the world safe for our economy and open to our cultural assault. To those ends, we will do a fair amount of killing.”

To appreciate the relationship between economic interest and cultural symmetry, culture has to be understood as a broad concept. English anthropologist Edward Burnett Tylor (1832–1917) defined culture as “that complex whole which includes knowledge, belief, art, morals, law, customs and many other capabilities and habits acquired by … [members] of society.” Culture is the way of life which people follow in society without consciously thinking about how it came into being. Robert Murphy described culture as “a set of mechanisms for survival, but it also provides us with a definition of reality.” It determines how people live, the tools they use for work, entertainment and luxuries of life. Culture is a function of homes people live in, appliances, tools and technologies they use––and ambitions.

It is, therefore, possible to argue that culture is about consumption in economic terms. Culture defines patterns of production and trade, demand and supply, as well as social design. Some examples are worth considering. In Moscow, the old Ladas and Wolgas of yesteryear began to be replaced by Audi, Mercedes and BMW cars in the late twentieth century. The number of McDonalds restaurants in Russia rose after the launch of the first restaurant in the capital in 1990. In Russia, China and India, luxury goods from cars to small electronic goods and jeans became objects of desire for the growing middle classes, while grinding poverty still affected vast numbers of their fellow-citizens. Consumption of luxury goods in China and India rose as their economies grew. Following the U.S.-led invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq, sales of American brands in Kabul and Baghdad increased. Such trends form an essential part of what defines societal transformation and, at the same time, represent a powerful cause for opposition.

The hegemon flaunts its power, but also reveals its limitations. It invades and occupies distant lands, but cannot end opposition from determined resistors. Economic interests of the hegemon, and the way of life it advocates, are fundamentally interlinked. The hegemon claims superiority of its own culture and civilization over the adversary’s. Its own economic success depends on the exploitation of natural and human assets of others. The hegemon allows political and economic freedoms and protections enshrined for the privileged at home. Indeed, the hegemon will frequently buy influence by enlisting rulers in foreign lands. Rewards for compliance are high, though human labor and life are cheap in autocracies of distant lands.

The costs of all this accumulate, and their sum total eventually surpasses the advantages. Military adventures are hugely expensive. As well as hemorrhaging the economy, they drain the hegemon’s collective morale as the human cost in terms of war deaths and injuries rises. Foreign expeditions by empires tend to attain a certain momentum. But a regal power is unlikely to pause to reflect on an important lesson of history––that adventure leads to exhaustion. Only when the burden of liabilities––economic, political, moral––causes the hegemon’s own citizenry to revolt does it mean that the moment for change has arrived. There is a simple truth about the dynamic of imperialism. Internal discontent turning into outright rebellion grows as the hegemon’s involvement in foreign conflicts gets deeper and its difficulties mount. On the other hand, radicalization of, and resistance from, the adversary seem to be in direct proportion to the depth of humiliation felt by the victim. Effects of this phenomenon are durable and unpredictable, such is the desire to avenge national humiliation. For whereas every human possession comes with a price tag, honor is priceless.

The historical development of the Middle East, comprising vast desert lands between the Red Sea and the Persian Gulf, is complex and messy. A careful survey of imperial designs from the early twentieth century, when the Ottoman Empire collapsed at the end of the First World War, leaving a void, to the present time is revealing. Historically, the Middle East has had two distinct spheres of cultural influence––Arabian and Persian. The Arab provinces had been under Ottoman control whereas Iran had been a theater of rivalries between Imperial Russia, Britain and France. A clash of interests between these major powers was the primary cause of upheavals in the last century.

The race for hegemony in the contemporary Middle East has its origins in the discovery of oil in Khuzestan in southwestern Iran in 1908. The leap of technology from steam to more efficient petrol engine gave new urgency to the search for oil. Khuzestan became an autonomous province of great strategic importance, but drilling had already been going on in anticipation of vast oil reserves in what is now Iraq and was then part of Mesopotamia. Nearly twenty years after Khuzestan in Iran, oil was found in Iraq in October 1927. And a decade after, vast oil reserves were discovered in al Hasa, on the coast of the Persian Gulf, in Saudi Arabia, which at the time was among the poorest countries in the Middle East. Imperial designs by great powers in the post-Ottoman Middle East became a certainty.

The demise of the Ottoman Empire and the discovery of oil in the Middle East were two major factors which would determine the course of history for the next century and more. Victory in the First World War was to destroy the existing balance of power, and any pretense of equality and fair play when there were clear victors and vanquished. With the prospect of the war turning in the Allies’ favor, a grand plan began to emerge. In May 1916, Sir Mark Sykes and Francois George-Picot signed what came to be known as the Sykes-Picot agreement, under which Britain and France were to divide up much of the Middle East between themselves, should the Ottoman Empire fall. That is what subsequently happened.

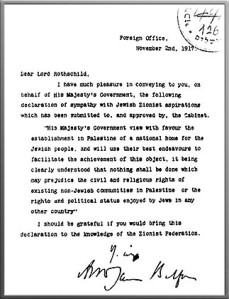

A year later, the British Foreign Secretary Arthur James Balfour gave an undertaking on behalf of the United Kingdom to Baron Walter Rothschild, a leader of the British Jewish community. Balfour wrote in his letter to Rothschild: “I have much pleasure in conveying to you … the following declaration of sympathy with Jewish Zionist aspirations which has been submitted to, and approved by, the Cabinet.” Balfour went on to say that “His Majesty’s government would view with favor the establishment in Palestine of a national home for Jewish people, and will use their best endeavors to facilitate the achievement of this object.” Despite words of assurance that this would not be at the expense of the Palestinians’ rights, contrary was the case. Jewish immigration and colonization of Palestine on a large scale was allowed and has continued since. By the time the state of Israel was established in 1948, the United States had become the most powerful nation in the West and the main backer of Israel.

The 1993 Oslo accords, which promised a permanent settlement within five years, barely limped to Oslo 2 in 1995, and finally collapsed. It was bound to happen, for virtually everything that mattered, the question of Jerusalem, the return of refugees, borders, security, and Jewish settlements, all these issues were left for future negotiations. All those issues still haunt the region. The Israeli-Palestinian conflict remains at the heart of the wider Middle East problem. And it can be argued that the fundamental nature of the cycle which started nearly a century ago has hardly changed.

[END]

You must be logged in to post a comment.